In ITSM, we’ve been talking about “products and services” for a long time. It seems as if these terms live together – you can’t state one without the other. But what do they really mean? Are they the same thing? How are they related? To figure this out, as usual, I’ll go off on a tangent older than most reading this post.

Forty years ago, Richard Clark wrote a seminal paper on instructional design in which he made the case that the medium of instruction had no effect on learning. He made this point famously when he stated, “The best current evidence is that media are mere vehicles that deliver instruction but do not influence student achievement any more than the truck that delivers our groceries causes changes in our nutrition .” But would we get any nutrition if the truck never came?

Robert Kozma, who believed that the medium DID matter, would say “no.” He engaged in a friendly debate with Clark over the next twenty years (e.g., ) which played out in a myriad of journals. Is learning realized through the message or the medium that carries it? To this day, the question is still unsettled in the research. But for me, the question was clarified during conversation I had with my librarian wife the other day:

David: “What are you reading?”

Allyson: “A book…”

David: “Is it a good book?”

Allyson: “Yes, why do you ask?”

David: “How do you know it’s a good book?”

Allyson: “(getting annoyed) Because the ideas in it are interesting.”

David: “Do you value the physical book or the ideas the book conveys more?”

Allyson: “The ideas, naturally.”

David: “But would you have learned those ideas WITHOUT the physical book?”

Allyson: “Well, I don’t really need the physical book. I could’ve read the words somewhere else.”

David: “Like where?”

Allyson: “Like another book, or heard them through an audio book, or someone could have told me.”

David: “So in each case, you need the medium of the printed words, the recorded words, or the spoken words to get the ideas?”

Allyson: “Well, yes. You have to have some kind of medium to transfer the ideas.”

I believe the Clark-Kozma debate lingered because the debaters always took one side or the other, never thinking outside the two halves of the question. But the real answer is that both the medium and the message are necessary for learning. The message contains learning (i.e., value) for the learner, which is transferred through the medium.

This story has a lot in common with the products and services puzzle confronting ITSM professionals. To set it up, in the “good old days,” the difference between products and services was pretty clear. As an example, software designers produced software products. Services such as order fulfillment and technical support were left to the “operational” side of the house to deliver and support the product. There was a clear conceptual definition between products and services. Products were “things.” Services were “actions”.

These days, with the proliferation of digital “things”, the boundary between products and services (or development and operations) is not that clear. Software has become more service-oriented with the Software as a Service (SaaS) model. In fact, many products are now delivered via the network. Other models (e.g., PaaS, IaaS, etc.) continue to evolve and gain dominance (that’s a lot of aaSes). Services contain both the thing being delivered and the delivery mode. So consulting services is a thing (i.e., advice) being delivered as a service (the engagement, communication, reports, etc.). Is there a difference between products and services, and if so, what is their relationship?

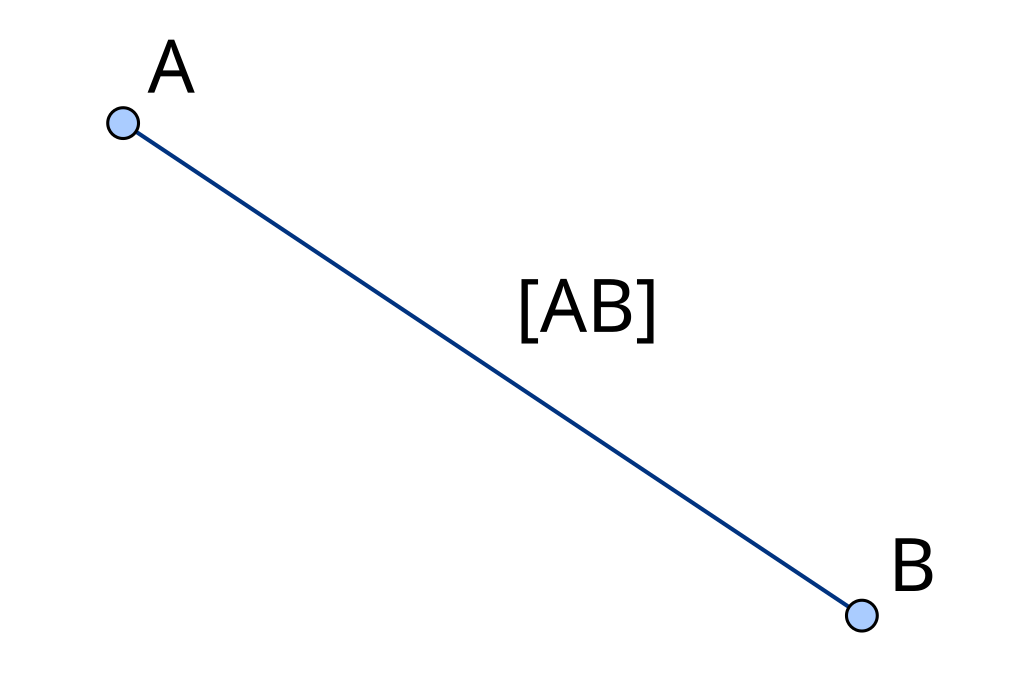

As true ITSM professionals, we can begin to answer this by asking from where does the value come? Is the value realized through the product or the service? I think digital products represent potential value to the consumer, but the value is only realized when it is delivered through a service. This service may take two forms – access or a service action related to the product. This is true even in the case of a good. The good must be delivered to a consumer for value to be realized. This delivery is a form of a service. Products by themselves are of no value in the same way that an axe is of no value unless you pick it up (i.e., access) and swing it (i.e., service action). Value is contained in products and delivered via services. You cannot provide value with only one – both product and service are necessary and related.