It’s been six months since the Crowdstrike outage – enough time to reflect on the incident and take stock. I had lunch with my CISO about a week after the outage. It was the first time we had seen each other in several weeks. “So,” I asked sheepishly, “how have you been since the outage?” “I’ve been fine. But the Service Desk has been swamped. Since my security team wasn’t that busy, we pitched in to help remediate the outage. They touched 15,000 servers and client machines in three days.” I inquired further. His role focused on the management of encryption keys that were necessary to unlock and manually patch the operating systems of the affected machines. “The hard part of the recovery was managing the keys,” he said. As his team was jointly responsible for the security of those keys, that was the extent of his involvement. You see, Crowdstrike pushed a bad patch – one file – but an important one that loads at the kernel level. This caused all of those Windows machines to “blue screen.”

Something didn’t compute. I thought he was going to be falling asleep at the table, eyes bloodshot, bags under them, a quart jug of coffee in his hand. Instead, he seemed rather chipper. Then it hit me. This wasn’t a security incident. Rather, it’s what we call in ITSM a deployment and release management issue. It’s not that Security Management wasn’t involved, they were. But it was apparent early in the Problem cycle that this wasn’t a cyberattack.

The response from our university IT was quick and appropriate. Within thirty seconds of the patches being applied, customers began to call and report “blue screens.” This spawned a number of related incidents at the Service Desk. These incidents were quickly correlated into a Problem record, which was upgraded to a major incident (i.e., outage) record in less than an hour, all of this happening around midnight on July 19th. During the early morning hours, an incident response team did a root cause analysis and quickly determined the problem was a vendor patch.

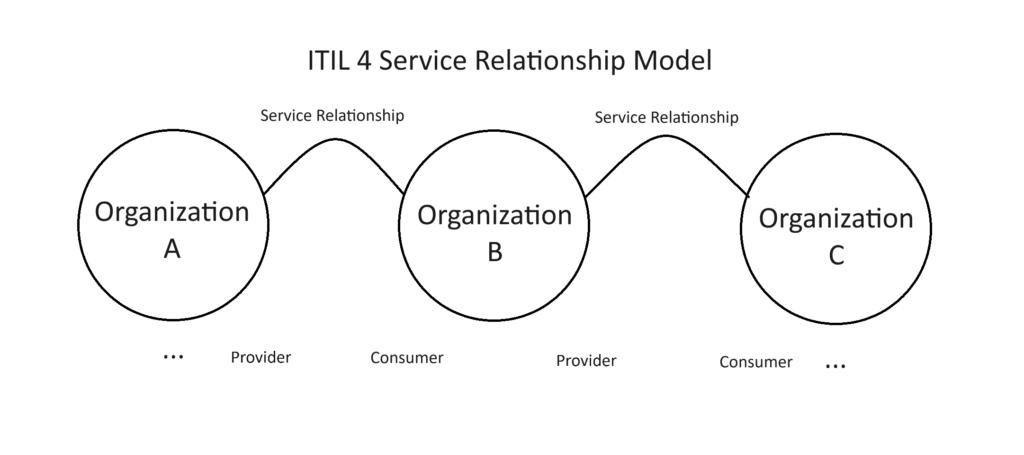

The vendor response was quick and the patch was available by early morning, although the CEO of Crowdstrike was criticized in subsequent days for not issuing a timely apology. The damage to Crowdstrike’s reputation was done. After all, the outage affected roughly 8.5 million computers. Crowdstrike was quickly seen as the responsible party and IT folks around the world became heroes as the outage response progressed. But Microsoft was also responsible for letting Crowdstrike play in the Windows kernel. Microsoft distanced themselves from responsibility by asserting, “Although this was not a Microsoft incident, given it impacts our ecosystem, we want to provide an update on the steps we’ve taken with CrowdStrike and others to remediate and support our customers.” In this instance, Microsoft was acting as an integrator, more specifically, as a Service Guardian, where they managed both a third-party vendor (Crowdstrike) and provided services (Windows). In this instance, ITIL best-practices dictate that we have a high-level of communication and trust with the integrator, but also acknowledge that our customers will hold us – not our vendors – responsible. After all, who are our customers going to blame – us or our vendor?

I see a double failure here. Crowdstrike failed by deploying a service with a critical bug in it, which they should’ve uncovered in their acceptance testing. This is not George Kurtz’s first high-visibility failure. In 2010, he was CEO of McAfee when a similar outage occurred. The second failure was Microsoft’s mismanagement of their vendor. One may ask why they allowed a vendor to deploy a file at the kernel level without sufficient testing. You would also expect Microsoft to have caught the error prior to approving the release of the errant file. Was Microsoft’s trust of Crowdstrike so great that they didn’t do acceptance testing and simply passed the updates through? If so, they need to review their Deployment and Release Management practices. Of course, this is pure speculation.

Meanwhile, back at “the ranch,” the IRT created a Change Request that included testing of the patch on a number of machines. Procedures to apply the patch were documented at both the individual asset level and the more strategic coordination level. On the communication side, customer communication began as soon at the Problem was identified, about an hour into the incident, with a number of communications happening in the early morning hours via IT staff in the colleges and university communications to stakeholders. Communication continued through the next few days as the incidents were remediated and non-reported servers and endpoints patched. An After Action Review was conducted less than a week after the initial incident was reported. Lessons learned were documented. DONE!! YAY!!!

Since I retired from IT, I’m an “observer” these days and I can tell you that I don’t miss the excitement surrounding outages. Been there, done that, got the t-shirt. But I must say that I’m very proud of the way our university handled this major incident – responsive, professional, by the book. I don’t think our response would’ve been as good five years ago. We’ve come a long way in our journey in understanding ITSM.

In summary, what ITSM practice areas were involved in this outage?

- Service Desk

- Incident Management

- Problem Management

- Continuity Management (via Major Incident/Outage)

- Vendor Management

- Asset Management

- Relationship Management (i.e., communication with stakeholders)

- Change Management

- Security Management (indirectly)

This is a pretty impressive slice of the ITIL ITSM Practices for a single issue. I think our IT folks would report that we have varying levels of maturity in each of the Practice areas, but I can tell you from experience that this kind of outage hones our skills to respond better the next time. Iron sharpens iron.