I was talking to a senior IT manager the other day when he lamented that younger managers under his charge didn’t communicate effectively. My colleague, a retired Air Force officer, remarked, “They want to give me a dissertation every time they report. I don’t have time for that. All I need is two points and a poem.”

I was intrigued. “What does that mean?” He replied, “Be prepared, that is, think about what you’re going to say before you enter the room. Be concise. Speak with executive function. Give me the ten-thousand foot view – I trust you with the details. Summarize your points and be done with it. In essence, move with a purpose.”

To further process this, I did some searches for the phrase and found two sources. The first was a reference to a traditional expression in homiletics (i.e., three points and a poem) that describes the shape of a sermon. Basically, the minister would present three main points of the message and then conclude with a poem or memorable anecdote to reinforce it. This seemed to me a logical etiology of the phrase, but why would my colleague reduce it to two points? Perhaps this was “military efficiency” at work?

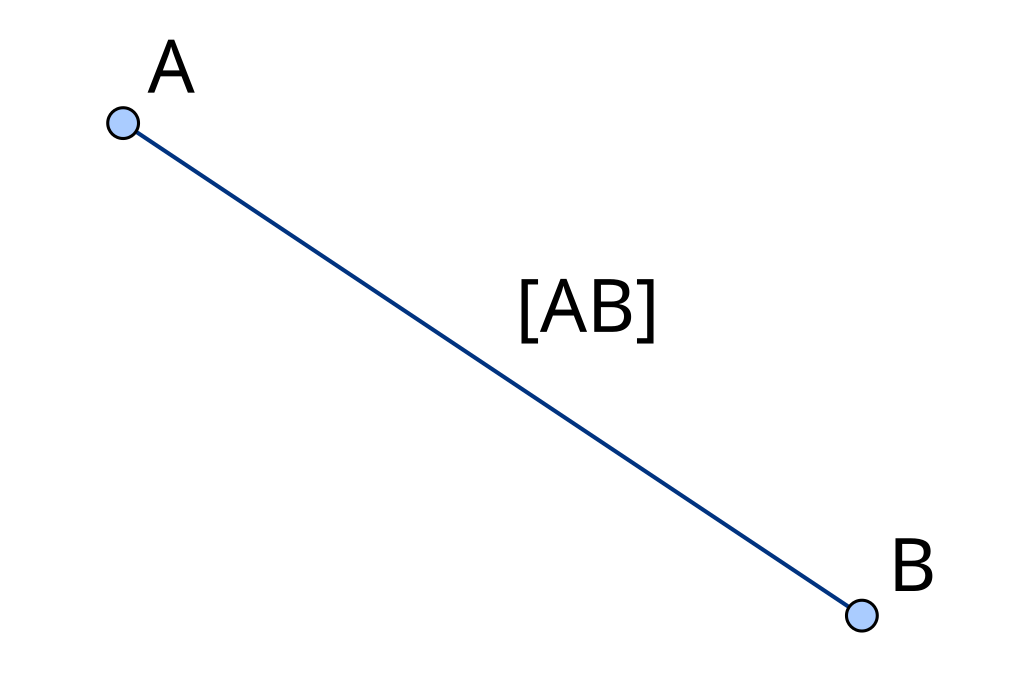

“A poem is a ‘line’ between any two points in creation.”

― Charles Olson

The second reference was a quote from Charles Olson (1910–1970), an influential American poet; “A poem is a ‘line’ between any two points in creation.” While it was unlikely that this quote was the source of my friend’s order, it gave me an interesting thought. By limiting the report to two points and connecting them figuratively with a poem, don’t we create the most efficient metaphorical figure? To my mind, the figure of speech had become a poem itself with mathematical precision and beauty. So the next time you’re reporting a project status to your boss, give her the mathematical elegance of two points and a poem.

Prepare, be concise.

Two points and a poem's grace

Speak with purpose clear.

-Dain B.